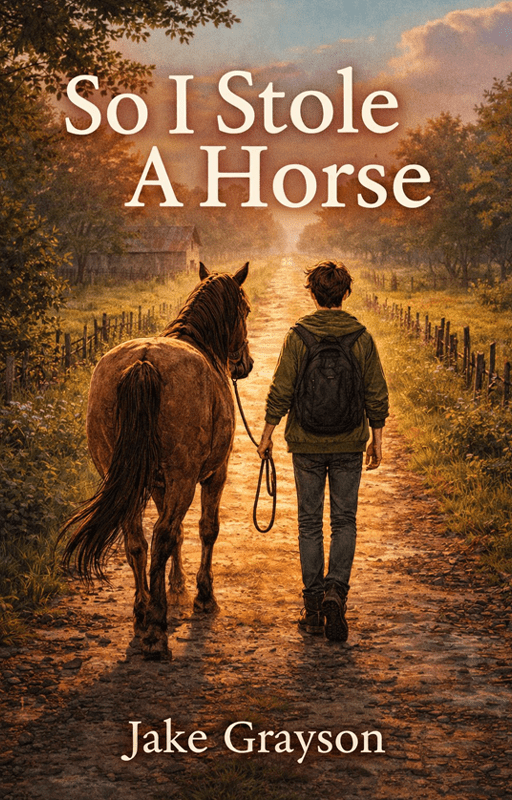

Let me just start this off by saying that I didn’t intend to steal a horse. OK? It wasn’t planned, it wasn’t plotted, it just sort of happened.

We were going to my grandparents’ house for the weekend. They live in this boring little village in the middle of nowhere, but Mum said we had to see them because they’re “family” and that the “countryside air will do me good after almost getting arrested” or whatever.

Anyway, once we got there, we unpacked our things, and I went to my grotty little spare room from the 50s. It wasn’t long before Dad came upstairs and started lecturing me about being unsociable, and that the reason I keep getting into trouble is that I don’t respect the people around me.

Well, let me know when you start respecting me, Dad, and I’ll see what I can do.

I didn’t say that out loud, of course, but that would have been funny.

“You need to be brought back down to earth before you become a proper adult.”

“Look at me when I’m talking to you.”

“You’re 17, act your age.”

“Stop slouching.”

He kept going on like that for 700 years, until I eventually got bored and walked out on him. He shouted something, but I already had my earphones in.

I felt strangled in that cottage, and the smell of Grandma’s broccoli soup wasn’t helping, so when no one was looking, I slipped out of the front door, and I went for a walk on my own.

It was pretty boring, there aren’t any shops in my grandparents’ village except for this little corner shop that I have avoided ever since the old lady who runs it said how she wished “more pretty boys would come into her shop and browse her goods”.

I walked up and down the streets for about 10 minutes, cursing my stupid life, when I saw a rusty gate at the edge of the village that led down a hill. I wouldn’t usually wander into the wilderness because I don’t want to get rabies, but I needed to kill more time, and I wasn’t ready to let my Grandad know that I got fired from the pub. (Just for sneaking chicken into the vegetarian soup, but that snobby mother was asking for it, and how was I supposed to know she had alpha-gal syndrome? She certainly wasn’t an Alpha Gal.)

I stumbled down the steep hill’s bumpy, muddy path, tripping on a couple of protruding stones, and, after passing through a gap in the hedge, ended up on a long, straight road with a bunch of farms along it.

Most of the farms were quite fancy, with neatly kept fields, pristine tractors parked next to other equipment I don’t know the name of, and grand farm houses. They were all almost identical, except for the one at the end of the road.

I would’ve thought it was abandoned if it weren’t for the surprisingly flashy car parked out front, which I can only assume was bought with what Mum calls ‘dirty money’.

Missing slates from the barn roof exposed rotting beams holding up the sad structure, and a pile of engine parts in the front yard told the story of a failed attempt to upgrade the old tractor, which sat slumped and rusted behind a pile of empty crates tangled in some barbed wire strung carelessly to one side.

In the garden to the left of the grotty farmhouse was a trampoline with a large tear in the net. Next to it sat a rusting, semi-dismantled swinging bench which must have been pulled over by a heavy gust, and had since been swallowed up by thistles from the overgrown hedge.

It was a right dump.

As I kept walking, I saw a field on the other side of the sagging barn. Well, I assumed it used to be a field. It looked more like an unkept, patchy, worn green carpet. Half of it was flooded, covered in sloppy mud that had begun to rot the wooden poles that kept up the barbed wire fence. Throughout the field were piles of animal waste, some of which looked like it had been sitting there for months. And standing in the corner was the horse it had all come from.

It looked how I felt, bored. At first, I wasn’t sure if it was fully alive. It was just standing there, rocking in the wind. Its head drooped, its sad eyes looking across to the neighbouring field, which was full of juicy, knee-length grass. It went to take a bite of grass at its hooves, but the stuff was so short, and it lifted its head in defeat.

Its chocolate brown coat was longer than I would have expected for a horse, especially in the summer. They always look so smooth and shiny on the TV, but this one was in desperate need of a barber.

Despite the long hair, I could still see its ribs protruding out of its sides, and even though it was on the other side of the field, I could still make out the cloud of flies around its face. The poor beast made no attempt to shake them away.

After a few moments, it looked up at me. I gave it a wave, don’t ask me why. I don’t really like animals, but this sad horse was better company than my Grandparents and their old-fashioned opinions. But yeah, I guess that was the nicest thing anyone’s ever done for this horse because it started trotting over to me. At the time, I thought it was going to attack me or something, so I just quickly hurried off. I looked behind me as I made my way back down the road, and I could see its fly-infested eyes still watching me right until I reached the hill.

I don’t know why, but that night I kept thinking of that stupid horse, with its stupid big, brown eyes. I kept seeing it standing there in the dead of night, alone, its bony legs rotting at the ankles from the damp ground, its eyes swarming with flies. It’s ribs.

The next morning, I woke up to the sound of my Grandma shouting down the phone to her friend Deardry, who I thought died about three years ago, but is apparently still among us. I got up and changed, and I can’t lie, the only thing I wanted to do was see that skinny horse. I needed the peace of that quiet road.

After breakfast, which is the only saving grace my Grandparents have (no one can beat their fry up), I stuck my trainers on and was about to head out the door when I thought that I should probably take some food for the horse (and I know it’s soppy, shut up).

My grandad grows his own vegetables in the back garden because he finds it more entertaining than playing video games, for some reason. So, I went to the kitchen and grabbed a couple of carrots when no one was looking. I stuffed them into my pockets and darted out the door before anyone wondered what was protruding out of my trousers.

It didn’t take long for me to make it back to the lane. It was windier, but dry, and my first thought, after being annoyed that I didn’t bring a jacket, was that at least the breeze might dry up that damp excuse of a field…

There I was, making the effort to walk to a random horse with carrots and thinking of its well-being. The countryside air must’ve been making me ill.

As I approached the farm, I noticed a badly botched 2006 Ford Fiesta parked up front. It looked like it had been through some cheap plastic surgery for cars, and it sounded like it smoked twenty packs a day. A terrible attempt at a conversion, I could only imagine.

A guy was standing by the driver’s window, his hands in his pockets in a shifty sort of way. The other guy, who sat in the car, was rummaging around before passing something to the farmer boy, who looked about 16. As I wearily drew nearer, I caught their attention, and in a final cheerio, the botched car sped off, coughing and spluttering into the distance. The farmer boy retreated into the farmhouse, where I could hear a dog barking angrily.

Once the coast was clear, I crept up to the field where the horse resided. I couldn’t see it at first, but then I saw its large head poking around the doorway of the small stable. Immediately, its ears perked up. Weirdly, it felt like it was the horse’s version of smiling. I pulled one of the carrots out of my pocket and waved it in the air, trying to keep on the down low in case anyone was still lingering. The horse took one look at the carrot and began trotting over to me. My heart did the same little jump as it did the day before, telling me to leave, but its trot was so springy that I felt surprisingly safe.

Horses are big. As it got closer, I realised I had severely underestimated their size. Its eyes were fixed on the carrot which gingerly held out. The horse did not delay in grabbing the thing with its giant teeth and snapping it in half, crunching down on the vegetable. I jumped back, dropping the rest of the carrot on the floor. Before I could pick it up, the horse bent down to grab it, but it was just out of reach. It stretched its long neck as far as it could. It was then that I realised the barbed wire digging into its chest, the whole fence bending with the horse’s strength. “Careful!” I said, reaching for the carrot and, almost instinctively, holding my hand out flat so the horse could pick it up. It was an odd sensation, feeling the things fuzzy lips tickling my palm. I almost recoiled, but I was too transfixed on the dark eyes. I saw myself in them, and I was smiling.

I fed the horse the second carrot with more confidence and even stroked its nose with my other hand. It was soft, but incredibly dusty.

In desperate need of some hand sanitiser, I stepped back as the horse stood up straight and looked back at me, giving a long, satisfied “Brrrr” with its lips.

“You’re welcome,” I said back. I stared back at it for a while. It didn’t budge. “Oh, I don’t have any more, sorry.” Still nothing. “You can go back to your stable now.” After a few moments of the awkward standdown, I hurried off back home, feeling guilt but not daring to look back at the horse, which was undoubtedly staring after me.

“Did you have a good walk, dear?” my Mum asked when I returned home.

I shrugged, “Not bad. A bit windy.”

“Where did you go? Not up to any funny business, I hope,” grumbled my Dad behind his newspaper. I felt my eyes narrow.

“I went for a wander around the farms, had a look at the animals,” I said back, a slight sharpness to my voice.

“Oh, lovely! Did you see the piggies and the horsies and the sheepies?” sang my Grandma, “Do you know what sound a sheep makes?”

“He’s 17, Mother,” said Mum. With that, I took myself back to my room. Throwing myself onto my bed, I couldn’t think of anything other than that horse, neglected in that field. The owners, if you could call them that, were far too busy doing dodgy deals to take care of it. Did they even know it was there at all?

My thoughts are cut off by my Dad, who once again, knocklessly invited himself into my room. I said nothing to him as he shut the door behind him and sat at the foot of my bed.

“I’m glad to see you’re getting some fresh air.” He said. I didn’t reply. I just stared at the ceiling, watching a small spider building a web in the corner of the beam. He took a long sigh and continued, because my lack of a response wasn’t enough of a message to go away, “Look, I’m sorry if I was too harsh yesterday. Your mother and I are worried about you.”

At this, I sat up. “Worried about me? How about before worrying about me, you try loving me for me? And stop comparing me to my brother. I’m not smart, and I’m not going to university. I don’t do well in customer-facing roles, and yes, maybe I do sometimes go too heavy on nights out. I know that was a mistake. I’m not perfect. But maybe try seeing what I’m good at before judging me for my flaws.”

At this, my Dad raised his eyebrows, “OK, and what are you good at?”

My mind went blank, and only one thing came to mind: “I can talk to horses.”

The third day of our stay in the village from the 18th century brought stormy skies. It felt thundery, but the rain hadn’t started yet. I was determined to get out to visit the horse again, even if it meant getting wet. It was better company than my Grandma and her ‘stormy snuggle blanket’.

“Oh, I don’t think you’d better go out today, son, haven’t you seen the weather?” Mum called from the sofa. I was midway through putting my trainers on at the front door, carrots already stuffed into my jeans. “Anyway, you’ve hardly said a word to your grandparents, and we’re going home tomorrow!”

Thank God.

“I’ve talked to them plenty!” I say in pretend offence. I turn to Grandad, who’s slumped on the sofa, trying to change the channel with a calculator. “We had a great long discussion about the football, didn’t we, Grandad?” Grandad sat up with a snort, his glasses askew on the tip of his nose, “You know? The game where we won 4-0?”

“Ooh, yes. What a game that was! Always good chatting, Sonny Jim.”

That conversation was three years ago.

“I’ll be quick,” I reassured my Mum, swinging the door open and darting outside before she could object.

It wasn’t raining when I stepped into the street, but it was indeed stormy, and as I made my way to the gate that led me down the path to farm alley, a crash of thunder shuddered the ground and echoed across the open fields.

The wind began to pick up, too, heavier than it had been the day before. The kind of wind that makes it tricky to keep your eyes open or walk in a straight line. Kind of like the night I was almost arrested, but that wasn’t the wind that was causing that.

I knew there was something wrong before I saw it. I could hear its stressed neighs, its heavy hooves stomping around the field. Once the field came into view from behind the hedges, I saw the horse, bucking and thrashing about the field. I stayed hidden for a while, remembering its size, and the power those legs probably have.

Once it calmed down ever so slightly, another crash of thunder vibrated the ground, causing the horse to kick about again. I looked across at the stables. The door had been swung shut by the wind, meaning the horse had no sort of shelter.

In the midst of its outburst, the horse laid its eyes on me. I crept out from behind the hedge, pulling a carrot out of my pocket. The horse stopped kicking for a moment and watched me, quite still. The heavy wind blew its fringe and tail. It looked rather majestic.

In another moment, it started trotting over. I prayed no more thunder would sound with the beast so close. Luckily, I got enough time to spread my hand out flat and feed the horse a few carrots before another crash of thunder came from the heavens. I immediately jumped back as the horse began to buck and spin, smacking its hind legs into one of the rotting posts, which flopped over, pulling the barbed wire down with it.

Suddenly, things felt a lot more dangerous. Suddenly, there was no fence between the horse and me. We both seemed to be thinking the same thing as we stood staring at the now-empty space between us. I didn’t know what to do. I was frozen in place. If I moved, the horse might have followed me, but I also couldn’t bring myself to try to fix the fence and trap it again.

The horse, however, knew exactly what it wanted to do.

I hadn’t noticed the carrot that had fallen out of my pocket, and the horse quite happily trotted over the barbed wire towards me. I stumbled back, tripping over a rock and falling back with a thud. The horse gently scooped the carrot up off the floor and munched happily, before turning to me and trying to dig its huge nose into my pocket, where the rest of the carrots resided.

“Stop! Stop! Gerroff!” I said, trying to stuffle away from the enormous animal. But it was determined. I pulled the carrots out of my pocket and threw them across the dirt, “There, that’s all of them! Now go back to your field.” I said, getting to my feet and walking away, brushing myself off and, again, not daring to look back.

I’d walked past a field full of cows and was about to make my way up the hill when I heard echoey trots growing louder behind me. I knew what it was before I turned around, and sure enough, saw the brown lump a few hundred yards away, trotting happily after me. Eyes locked. Another crash of thunder sounded, but this time, the horse didn’t react as much, simply shaking its head as if in disapproval. Its full attention… was on me.

“Stop following me!” I shouted down the road. “Go home!”

Of course, it didn’t. The horse reached me before I could say anything else, nuzzling my pocket again for any sign of food.

Then I saw the headlights far behind the horses’ swishing tail. Not knowing what else to do, I jumped into the nearest field through an opening in the hedge, my new accidental pet happily in tow.

Its eyes lit up at the sight of the lush green waves of grass in front of us. I’d managed to get us well concealed before the horse came to a stop and sank its teeth into the juicy green stuff. The car chugged past, oblivious to the great escape happening just behind the shrubbery.

“Well, you seem quite happy here. And you’re not that far from your farm, so I’m sure they’ll find you soon enough.” I gave the horse a friendly pat on the side and returned to the path, checking through the hedge as I walked past. I could still see the shape of the horse, happily grazing in the field of its dreams.

Climbing up the hill only made the gusting winds worse, and by the time I reached the top, it felt like I had to swim through it, my trousers and coat flapping violently behind me. By that point, I began to feel the occasional raindrop on my face, and knew I’d make it back just in time before getting drenched.

I had just reached the gate at the top when I heard rustling at the bottom of the hill. I knew who it was before its long face popped up above the hedge. Ears pricked.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” I grunted to myself, stepping back into the field as my new friend began to wobble its way up the rocky path, its thin legs shaking as it tried to navigate its footing against the harsh winds, the rain getting heavier by the second.

“Go back! You’re going to trip!” I shouted, (I know horses don’t speak English), but it kept making its way up. I hurried down the hill as the heavens truly opened, and the downpour began, the muddy path soon becoming a stream of muddy water. I was just a few meters away from the horse when it took a shaky step forward, its hoof slipping off a smooth stone protruding from the mud. Its back legs, I noticed, had already gathered a mass of mud around them, and in an attempt to steady itself, the horse’s hind legs struggled to move and gave way, causing the beast to stumble to the side, crashing into the hedge as its hooves finally unclogged from the mud with a slurp.

I always knew horses falling over wasn’t a pretty sight. It’s the reason we never watch the Grand National, despite all my friends placing bets. My soggy friend wriggled in the hedge as I hurried down faster, its legs flailing in the air. I reached them as they finally gained some control of themself, now lying up against the hedge with its front legs tucked in.

“Are you ok?” I said in a gentle tone I didn’t know I was capable of, “Do you want to get up?” For some reason, the fact that the horse didn’t get straight back up concerned me. Didn’t horses usually sleep standing up?

But they didn’t budge. I tried giving them an encouraging nudge, but nothing.

I couldn’t leave it. But the rain was coming down so heavily now that I was practically blind. I crouched down next to the horse, gently stroking its neck. The hedge provided a bit of shelter from the storm, and I found myself tucking in close next to the horse, wrapping my arm around their back as they sighed, rain dripping from their snout.

We stayed like that for about 20 minutes: Just two lonely, soggy creatures hiding from the storm. Until finally it began to ease, and the sun finally peered out from behind the wall of grey.

“Feeling refreshed?” I asked my wet friend, who answered with a shake of their head, drenching me more than I already was. I laughed and spat out horse hair that had somehow made its way into my mouth, “Gross!”

We were both shivering, and as I got to my feet, I watched with bated breath as my horse readied themself before lifting off the ground with a snort, their legs still wobbling on the uneven terrain. “Well done!” I said, patting their side, “Now, let’s see you walk.”

I kept my hand on the horse as we climbed uphill. For some reason, the idea of climbing down with the rushing water felt more dangerous, and I didn’t want them to fall again.

Somehow, we reached the gate, and as I swung it open, I allowed the horse to pass through, back out onto the steady ground of the road.

“Are you limping?” I asked worriedly. I couldn’t tell for sure, but it looked like they were putting less weight on the hoof they slipped on. But they kept walking, and I continued to lead them.

I had no idea what my plan was when I reached the front door of my grandparents’ house. The horse gave me a little nuzzle of reassurance as I twisted the handle.

“OH MY GOD”

My Mum was at the door first, pulling me into a tight hug, “Where the hell have you… Where did you get that horse from?”

“It’s… a long story, it followed me home, and we got caught in the storm, I think it might be hurt, but–”

“What the hell have you done?” I heard Dad shout from behind Mum, “You stole a horse? Do you want to get arrested again?”

“I didn’t steal it!”

“You’re lucky the farmer didn’t shoot you! Stealing a horse, whatever next!”

“I DIDN’T–”

“Oh dear, would you look at the state of that poor thing, I can count its ribs from here, and I don’t have my glasses on.”

I didn’t even notice Grandma’s little head behind my Mum’s shoulder. She slowly came forward and took the horse’s face in her little hands. “Where is he from?”

“One of the farms at the bottom of the hill.”

“The one at the end?”

“Yes.”

“I should’ve known. Dodgy place down there. Been mistreating their animals for years. They used that old place to do funny business, you see. Bring animals in as an act.”

“So that’s where you were going.” Dad started, “Couldn’t keep away, could–”

“Shut up, David.” Snapped Mum, “He saved this creature.”

The horse gave a huff of approval, nuzzing my arm again, forcing me to stroke his head. Dad backed off in his own huff.

“What do we do?” I asked Grandma the horsewhisperer.

“Leave it to me. Let’s get him into the back garden for now. There’s a path around the side. I’ll call animal rescue. They’re familiar with that farm and won’t question coming to deal with this beautiful creature.

“They won’t put him down, will they?”

“Oh, certainly not. He’ll shake off that limp soon enough. Been through worse, I expect.” Grandma gave the horse a stroke down the side, “Needs a shave,” she said, examining its chocolate coat. I smiled as she looked at me, “The horse does, too.” She winked.

People came and took him away the next day. I gave him one last carrot and a hug before Grandma and I watched the horsebox drive long into the distance. I was sad to see my friend leave me, but I was happy he was getting the life he deserved…

Of course, it wasn’t long before I began visiting him at the sanctuary. I even started to volunteer there a couple of times a week, in between shifts at my new job. He’s quite fat now, actually, and he’s made friends with some other horses, and a donkey named Derek. The flies have stopped pestering his eyes now, and Dad has stopped pestering me, and his chocolate brown coat is shinier than it’s ever been (the horse, not my Dad, who’s going greying by the second.)

I named him Cocoa.

One thought on “So I Stole A Horse”