Friday 8th December 2023. It’s been another dull winter’s day, not just in the weather, but in the mood, almost as if the clouds themselves are joining us in anguish. It’s a day that we’ve all silently been preparing for over the last four years, though I don’t think any of us truly expected it to arrive.

Four years ago. It was almost the exact day that Mum first started feeling back pain. It was her birthday. It was a chilly but clear winter’s morning. She and I had gone for a walk along the canal and then to a garden centre that we traditionally go to at Christmas time. The doctors first dismissed it as indigestion and recommended peppermint tea and mints to help move things along. She’d be back to normal in no time.

Today, the four of us sit around the hospice bed that my Mum sleeps in. She won’t be waking up.

Her skin is greyer than her short, wiry hair, which was once long, blonde, and healthy. Her face is sunken, and her arms emaciated, any muscle she’d gained from her healthy life prior now a distant memory. Lying on her back, the bed tilted up slightly, her mouth droops open as she breathes heavily in, out, and in, and out, with terrifyingly long breaks in between. It’s hard to believe that the lady lying in that bed is the same lady who briskly strode next to me on countless nature walks, who won horse riding competition after competition, and who raised three children with less help than she deserved.

Despite all of this, her skin is warmer than ever. A variety of soft blankets cosily cocoon her in her thick Snoopy jumper, which she bought at a local charity shop – she loved a charity shop – to keep her snug on this otherwise cold, bleak winter’s night.

She occasionally shifts her position, sometimes letting out a small huff or murmured moan, a little reminder of her voice. Sometimes, it sounds like she’s in pain or wants to wake up, trying to fight the morphine being pumped into her body, but the nurses assure us that she’s comfortable—more comfortable than she’s been for a very long time.

None of us want to talk, but we don’t want to sit in deathly silence, either, with the only other sound being the morbid hum of machines or busy footsteps tapping up and down the corridor outside.

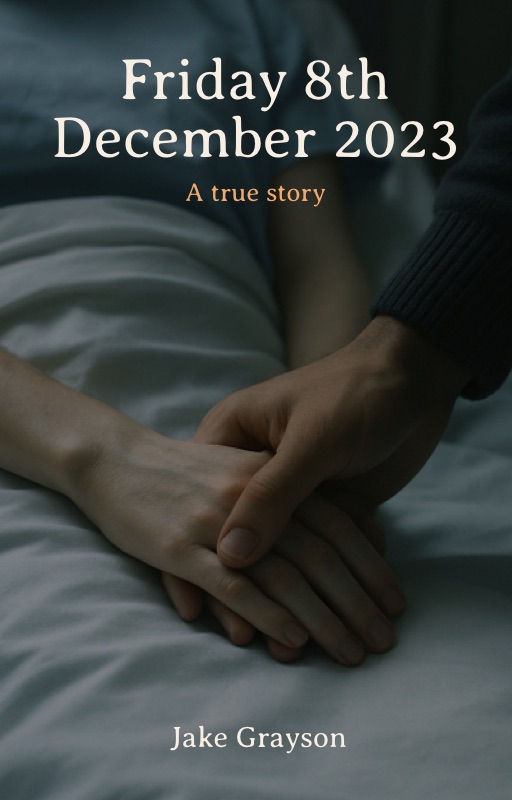

We take it in turns to hold her hand. As I wrap my fingers around hers, I try to take in every small detail of her skin. Her warm hands, her slightly rough palms from years of hard work, her thin arms that house moles or perfect imperfections that, soon, I won’t get to see anymore. I don’t want to forget any of them. Any of her.

Eventually, unable to bear the melancholy, we switch on the television, which airs repeat episodes of The Big Bang Theory—a common and comforting sight at home. It’s a fragile attempt to raise our spirits and distract ourselves from the pain in this strange environment. A pain that will undoubtedly linger for many years to come.

We try to talk about life before – about funny stories and things that Mum enjoyed doing. We talk about gardening, her favourite pastime, and I think back to the common sight of her on her hands and knees in the flowerbeds, bringing the garden to life. I remember how much joy her irises brought her when they bloomed, and her elation when her waterlilies flowered for the first time. At the mention of gardening, she lets out a long moan as if approving of the subject. Coincidence or not, it makes us smile – and breaks our hearts.

The conversation inevitably shifts to what might happen next, about other people who have lost a parent, how they’ve handled it, and what we need to prepare for. We’re getting into the dreary details when my younger sister chimes in, worried that we’re upsetting Mum by discussing such things in front of her. I think about it, too, about how, even in her current state, she won’t be worrying about herself; she’ll be worrying about us.

My thoughts turn to my sister as I watch her sitting next to the bed, gently nursing Mum’s sore ear from weeks of lying on her side. She brushes the short hair out of the way, “It’s actually getting quite long now.” She says, stroking her head, “She didn’t think it was growing back, but it is.”

She’s 19. A teenager. About to lose the only female role model she truly has. The image of her face when she first walked into the room with my older brother still burns into my memory.

My brother sits in silence in the corner of the room. He’s never been one to show much emotion, but occasionally, he gingerly approaches the bed and takes my Mum’s hand, clearly feeling rather awkward about the situation. No one says anything, though, I’m sure he’ll process it properly when he’s alone. We all will.

The nurses come in now and then, their spirits remaining professionally high. They talk to Mum as if she were awake and alert, letting her know when they’re feeding her or giving her water. From time to time, they come in and massage her legs to keep them well-circulated. A friendly smile always spread across their faces. But despite their respectful attitude, it upsets me, and I feel embarrassed for my Mum. It’s a sad sight to watch them put lip balm on her or wipe the drool from the corners of her mouth. Both are such small tasks that Mum should be able to do without a second thought. I know she’d hate to have so many people watching her sleep, she’d hate to know we’re watching her getting fed. She’d hate to be seen so incapable.

At some point in the day, almost as if on cue, the heavens open, and it begins to rain.

After going home for dinner and a much-needed break from the emotions, my sister and I tentatively return to the hospice to find my aunt, Mum’s older sister, and uncle have joined my dad in that same wretched room. He hasn’t left her side all day; it’s hard to tell if it’s out of love or out of guilt. My brother must have gone home for the night; he’s never been a fan of hospitals.

I’m once again hit with the shock and overwhelmingly grave emotions as the first time I lay my eyes upon my Mum this way, my chest goes tight trying to hold back the tears. It still doesn’t feel real.

Her position has changed slightly; she’s tilted to the side, looking a bit more like she’s sleeping naturally, but her mouth remains open and drooped. Her breaths seem to be getting further and further apart, each break sending bolts of fear through my body that it’ll be the last.

My mind is fuzzy after the abnormal day, and I don’t take in much of what is being said. I just stare at my Mum. My beautiful, wise, kind, reliable Mum. My Mum, who was always there for me. Who always put others first, even when she shouldn’t. Who made me laugh, who gave me confidence, who made me feel safe and wanted. Who, four years ago, I went for a walk with on her birthday, neither of us knowing what was just around the corner.

It begins to feel like it’s being dragged out, and part of me hoped the inevitable would have happened whilst we were away. My aunt says that Mum is trying to hold on for us, having sat with my Nana in a similar situation only a few years prior, and that she just needs to let go. “Stop trying,” my aunt says to her sleeping sister, “Give up, just let go.”

Another half hour or so goes by, and my sister and I, sitting on either side of the bed, finally build up the courage to go home. Knowing that we’ll never see our Mum again. We take turns giving her a gentle hug, saying goodnight, and a kiss on the cheek. “Don’t worry about us,” I whisper, before letting go. “We’ll be fine.”

As we leave down the corridor, I turn around to get one final glimpse through the narrow window of my beautiful Mum, lying peacefully in her bed.

2 thoughts on “Friday 8th December 2023”